Adaptation is a tricky business. It is an exceedingly difficult task to translate the complex nuances of an artistic work from on medium to another. Countless problematic movies have shown that adaptation to film can be a stumbling point for even the most talented of directors. Conversely, great films have been made specifically to address the difficulties of using film to tell certain kinds of stories.

So it was with a mixture of trepidation and excitement that I patiently awaited the release of director John Hilcoat's adaptation of Cormac McCarthy's award winning novel, The Road.

I read The Road in the summer of 2007 and it quickly became one of my all-time favourite novels. The story places a father and son in a hellish post-apocalypse America, trying to make it to the coast and south in order to escape the encroaching cold of winter. The book is harrowing with its pessimistic depiction of the fall of mankind, and yet touching in its portrayal of a father and son who have nothing left but their lives and each other.

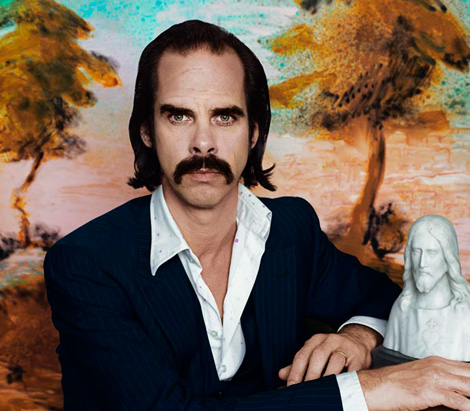

When I first heard that Hilcoat was directing the adaptation of the novel I was thrilled. His most recent film prior, The Proposition, is a dark and gritty western set in the Australian outback. The film explores the frailty and complexity of morality in a fringe society, and makes Hilcoat seem like a perfect fit for McCarthy's novel. Hell, McCarthy himself said as much. Additionally they cast the superb Viggo Mortensen as the father, and got Nick Cave to score the film. Even if you're unfamiliar with Cave's work, one look at him will convince you that he is the man to score an adaptation of The Road.

All the signs seemed to suggest that the perfect group of people had come together to ensure that The Road was faithfully adapted to film. Then came the production problems.

First a series of delays pushed back its release by a year, purportedly so that the special effects work could to be completed. Then the first trailer was released, and it portrayed a very different film than fans of the novel were expecting. The signs were not good, but I remained hopeful that the film would be a successful adaptation. When Hilcoat's The Road was finally released in late November 2009 I made sure to see it on opening day, eager to see how the novel had been translated to film.

The verdict? Well...

The film isn't bad per se. On the contrary, it is an effective and powerful visual representation of the basic story and thematic structure of the novel. While certain elements of the book were lost, toning the contents down slightly, the most important features of the story were all there. A commendable effort has been made to retain the core experience of the novel, and you get the a similar sense of both the most savage and noble aspects of the human creature. Yet despite that faithfulness to the source material, the film simply does not work the same way the novel does.

The majority of the people I saw it with did not enjoy the film. Those who had read the novel had mixed feelings; some loved the movie for its faithfulness, while others felt this only tarnished the best aspects of the prose by awkwardly depicting them on screen. The majority of those who had not read the book complained that the film did nothing for them emotionally. It failed to inspire, awe, or do anything more than keep them vaguely interested in the plot for its duration. At best the film had moments that shocked them, though only through their sheer conceptual grisliness. The same events in the novel had a primal, gut-wrenching effect that was lost in the transfer of mediums, and that's really where the problem lies.

The Road, as a novel, is an emotional experience. At its core the text is a story about a man and his son trying to survive. The strength of the book is in the emotional resonance of the man and the son and their journey, and McCarthy achieves this by bringing the reader into to the fictional world. Their encounters emphasize how dire their situation is, and also show that more than just their lives are at stake.

McCarthy's writing style forces the reader to share their journey insofar as there is never any moments of respite between chapters or whatnot; the entire narrative is presented in an unflinchingly stark and continuous stream, much like how the characters experience it as their lives. He gives the reader a window into the lived-experience of the two characters, and their choices and attitudes present a moral discourse in the face of human depravity. They are the only two people we focus on, and the only ones who we can relate to a basically good. In the post-apocalyptic world they become not just as a nameless man and son but a symbol for humanity itself struggling to survive. By leaving them nameless and bringing the reader into the text with his unflinching narrative style, McCarthy's book achieves an emotional connection is lost in the film for a variety of reasons.

In the book the story is told by a semi-omniscient narrator, but it is largely embedded in perspective of the nameless father. At least initially this has the effect of making us identify and sympathize with him above all others, including the son, and so we understand his choices in the journey through the wasteland setting. As the book goes on, however, the son grows and begins to challenge his father. The narrative remains that of the father, but the son gives voice to the classic debate about surviving or living. Despite the continued understanding of the father's motivations we are forced to question his choices, and this gives rise to the question of humanity at the end of the world. Does it survive? Can it? The book raises these questions through the story of the father and son, but the answer is left in the hands of the reader.

The film, however, more or less answers these questions for us. The perspective is necessarily that of the unseen watcher, and the voice overs and flash backs that attempt to emphasize the father's perspective do little more than increase this sense of voyeurism. From the very beginning we are just as close to the father as we are to the son, and right away it is evident that Mortensen's character is willing to sacrifice anything for survival. The question of morality is present from the beginning but is only given asked later on when the son finally grows a voice, as dictated by the chronology of events in the novel. By this point the audience has already made up its mind about the idea of mere survival because they have already begun to question the father.

In the film version of The Road the audience is distanced from the father's perspective early on, and this runs counter to the novel's ability to bring the reader into the story. Rather than allowing the reader to invest and partake in the struggle, the film depicts a man who from the beginning shows himself to be strung-out and losing touch. The father's actions in the film are the same as in the novel, but the difference is that our understanding and judgement of them is different because we are not in his head; instead of sharing his experience we watch Mortensen act it out. Ironically the very power of his performance is what hinders its effect, as his obvious and sheer desperation prevents us from identifying with his character. Moreover the fact that he is a recognizable actor playing the role makes his namelessness largely irrelevant. Mortensen thus ensures that his version of the father is a powerful and convincing character, but not one that we can lose ourselves in and relate to.

This is once again a case where too much faith to the source material is a bad thing. The film attempts to follow the book to the letter, but the subtle changes keep the fidelity skin deep. With the father the change of mediums causes an increased distance between the audience and the characters in the film, thus hampering the emotional connection that is central to the book's resonant power. As McCarthy himself told Hilcoat, "a novel's a novel and a film's a film, and they're very different," and in trying to keep them similar the director hurts his film. Hilcoat did, however, make a number of changes to the text, ranging from minor details to the addition of an entire central character.

Charlize Theron has a major cameo in the film playing the mother, completing the family that the movie follows through the apocalypse. Her character was created specifically for the film, and represents Hilcoat's most significant departure from McCarthy's text. The problem is that the character of the mother doesn't really add anything to the film. She is still absent for the majority of the film and merely symbol of absence to her son, and she only divides the father's motivation away from his child. Her appearance signifies complete hopelessness to counterpoint to the son's insistent morality and the father's steadfast survival, but this role is already filled. Throughout the book the son repeatedly expresses his frustration at life and a desire for death, and his father tries to dispel this impulse. The only aspect of the novel that McCarthy insisted be retained in the film was an exchange in which the boy asks his father, "What would you do if I died?" The father replies, '"I'd want to die too, so you could be with me - so I could be with you." With these few lines of dialogue the father makes it clear that his continued survival is based only on his son; the boy eventually comes to disagree with his father, espousing the belief that mere survival is not alone worth living for. The father's ideology itself nurture's the son in his growth and ultimate rebellion. Theron's role in the film provides an additional symbol of surrender where there is no need for one, and does not serve the story in any other way except to answer the question, "What happened to the mother?"

This itself reveals the central problem with this film: it gives detail where the novel left ambiguity. Where before there was merely the absence of a mother there is now Theron's cameo. Where before there were merely lines there is now dialogue that the actors have given specific inflections. A story that speaks to the concept of humanity itself has become a film about Viggo Mortensen as a father and Kodi-Smit-McPhee as his son. The book is purposefully barren to encourage the imagination and the conscience of its audience, and that quality is lost in the film. Instead the film is a very specific tale about a father and son, and a moving one, but it is not the powerful and expressive story that was The Road.

The most egregious aspect of Hilcoat's film, however, is in the soundtrack. This is the one quality of the film that isn't simply a problem in the adaptation of a novel but rather an outright flaw in the film. I noted earlier that Nick Cave is responsible for the score, and that this seems like a match made in heaven. Cave's general demeanor and appearance literally project waves of brooding somberness, and this is perfectly reflected in his score for The Proposition. In that film the dangerous and barren landscape of the Australian outback and the troubled morality of the plot are accentuated by Cave's dark musical contribution. With only this admittedly limited experience of Cave's work I suppose my expectations for his score were somewhat exaggerated. That said, nothing could have prepared me for the sound of The Road.

For reasons that I can only snarkily and half-heartedly attribute to Oprah's praise for McCarthy's text, Cave decided to score The Road much like a motivational sports film. Almost every moment seems to be accompanied by a swelling orchestral flourish designed to remind us of how much adversity the man and son are overcoming by merely staying alive and maintaining some semblance of a moral high ground. Every track emphasizes the message evident in the film's second trailer, that "All of humanity has been reduced to hillbilly cannibals and yet these two people are still acting like good Christians, and that's fucking inspiring!" Every time the music starts building it is to the detriment of the film because it contrasts so distinctively and inappropriately with the dark, cynical, and largely understated subject matter. There is certainly a sentiment hope in The Road but it is subtle and whispering, not powerful and sweeping. When I read McCarthy's post-apocalyptic text it was necessarily without musical accompaniment, and after hearing Cave's score I prefer the silence. It suits the content better.

In closing, I'd like to reiterate that the film is not bad. Everything that matters from the book is there in some capacity, and it is still a powerful and chilling narrative. The problem is that Hilcoat's The Road just doesn't feel like McCarthy's novel. It doesn't the emotional resonance that made the book a Pulitzer-prize winner, and it doesn't have the contemplative tone that allowed the story of a father and son speak to all humanity. It isn't a bad film, it just isn't The Road, and that's too bad.

As Cormac McCarthy himself has said, adaptation is possible if you can just capture the essence of the source material. Hilcoat's film only sometimes achieves this, and only during the sequences without background music. If you haven't read the novel then do so first, but otherwise the film is worth seeing, albeit with lowered expectations.

No comments:

Post a Comment