Ok, so this rant just sort of kept going as I got more into it and my ideas got more developed. It’s long, but bear with me. Also don’t bother reading this if you haven’t seen the film or read the novel, I’m pretty explicit with my plot points.

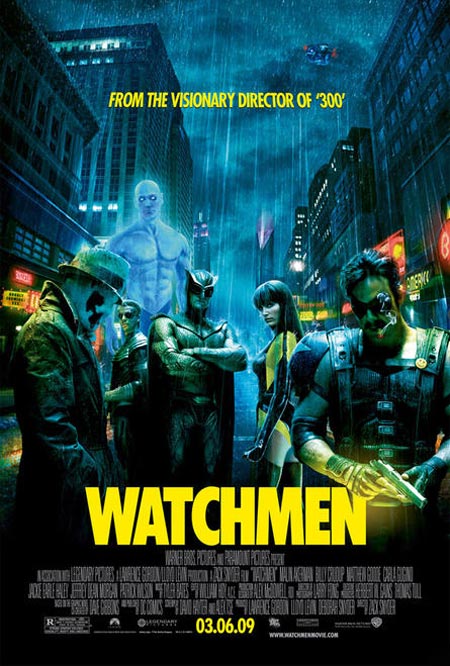

You could write entire books on Watchmen and its adaptation into a feature film. You could talk about the influence of the graphic novel, the cultural weight of the text, the exactitude with which it was crafted, and all sorts of other interesting aspects of the work of art that is quickly becoming franchised. You could talk about the history of its road to the screen, the merits of the final product as a film, what was cut out of the original text and the different versions of the film, the marketing, ad infinitum. What I’m going to talk about are a few moments and aspects of the film that reveal the overall approach to the original text and the resulting thematic feel of the film.

A lot of what the film actually does right has an estranging effect, distancing the audience from the art instead of bringing them into it. Throughout the entire three-hour affair I had an eerie, unshakable feeling that I was gazing into the uncanny valley. Everything is a picture-perfect representation of the graphic novel, from the costumes to the setting to the mise en scène, and that is actually one of the most glaring flaws of the film. There are differences between the mediums of film and graphic novel, and Zack Snyder and co. have done little to account for them. While this does not ruin the movie or the story by any means, it does mar the effect of it. For example, the Minutemen appear exactly as drawn, and instead of evoking a sense of nostalgia, as they do in the book, they again estrange the viewer because they seem so incredibly ridiculous. More profound than the visuals, however, are the times when Snyder’s adherence to the original work damages the story on a tonal level.

At the screening I attended, when Rorschach tells the prison inmates “I’m not locked in here with you, you’re locked in here with me,” most of the people in the theatre actually laughed. This was not the response his words should have elicited, and a big part of the mistranslation was in the transfer of mediums. In the book Rorschach’s words convey all of the terror and dread that the threat of such an obviously and recently dangerous psychopath should through his powerful delivery, or lack thereof rather. The audience doesn’t actually see him make the statement, but rather hears about it through the reflective writings of the prison psychiatrist.

Rorschach’s words are not merely a physical threat but also a statement about the gravity and ferocity of his politics, and they resonate with the psychiatrist so strongly that they slowly deteriorate his marriage and ability to exist in his contemporary American society. The chapter they appear in is concluded with the Nietzsche quote, "If you look long enough into the void the void begins to look back through you," appropriately alluding to the personal and collective implications of Rorschach’s existence. In the context of the novel, on the page, Rorschach’s words convey a harrowing sense of Rorschach as an individual and the seriousness of the situation.

When the same scene plays out on film, however, the statement is merely a brutish threat, as though Rorschach is making sure to beat someone up on his first day in jail to avoid becoming someone’s “bitch.” The entire subplot with the psychiatrist is cut out of the film without seriously degrading the overall story, but the changes to the context and delivery of the line are monumental. The audience I was with found Rorschach’s statement laughable even despite their audible cringes only seconds before when Rorschach poured hot grease on his fellow inmate. Perhaps it was the fact that the threat originates from a skinny ginger doing his best Christian Bale voice, or that he is surrounded by the cast of Oz, or that his delivery is punctuated by an almost vaudevillian slap in the face with a nightstick, but Rorschach’s imposing line simply does not work on film. In fact the entire prison sequence comes off badly, with the climactic murder of Big Figure playing out like a humorous wink at the camera. Rorschach is less the pure force of nature that he was written as, à la Heath Ledger’s anarchic Joker, and more a deranged Saturday morning cartoon character, so wacky that you never know what kind of mischief he’ll get up to next (murdering a midget while he goes to the bathroom, for example).

Jackie Earle Haley is fantastic as Rorschach, his performance is note for note perfect, but with his slight figure, poor grammar, and dialogue that becomes ridiculous when voiced aloud (“This awful city, it screams like an abattoir full of retarded children”), the character is often inappropriately comical in the context of the realistic film. It is the very literalness of the representation of the character on screen that hampers his effect. Robert Frost said “Poetry is what gets lost in translation,” and that seems like an apt summation here. Thankfully, though, it is not applicable to the entire movie.

The film does a very good job of conveying the complexity of Dr. Manhattan and his increasing detachment from his human origins through the impressive performance of Billy Crudup. In some ways the film exceeds the graphic novel: Dr. Manhattan feels more like an omnipotent being in the movie than he comes off on the page through the animation of his spectacular feats and the audible delivery of his lines. Crudup’s often unaffected vocal delivery gives a literal and tangible humanness to the character, more effectively evoking the sense of a lapsing human being and mortal. With the exception of a few brief moments of unnaturalness, Crudup maintains a presence that is subdued, contemplative, and waveringly indifferent, the very essence of Dr. Manhattan. His origin story is truncated and unaffecting, and his increasingly ambiguous temporality is almost completely lost from the story, but it only speaks higher of Crudup’s portrayal that the character remains so powerful, sympathetic, and awe-inspiring in his indefinite position between divinity and humanity. The feel of his character shines through as one of the most effective and respectful aspects of the adaptation.

Salman Rushdie's recent article in The Guardian discussed the tricky business of adapting novels into films, and he observes that “an adaptation works best when it is a genuine transaction between the old and the new, carried out by persons who understand and care for both, who can help the thing adapted to leap the gulf and shine again in a different light.” After seeing the film there is no doubt in my mind that Snyder cares for Allan Moore’s original graphic novel, and his treatment of the adaptation leads me to believe that he very much does understand the content. In a lot of places the film took liberties from the original graphic novel that worked to its advantage: not having Rorschach ape the final horrific moment of Saw was a wise choice, for example.

Snyder clearly felt he understood the original work enough to make minor tweaks to it in order to make it work better on film, but therein lies the problem: he only made minor tweaks. Rushdie also warns that “Those who cling too fiercely to the old text … are doomed to produce something that does not work, an unhappiness, an alienation, a quarrel, a failure, a loss.” The insistence upon visually and structurally capturing the original graphic novel as written is the film’s most serious flaw, creating a sense of the uncanny that unsettles, amuses, and above all distances the audience from the art. With all that in mind, I want to discuss the ending.

So they changed it. They changed the ending to Watchmen… Once the initial shock has dissipated it’s easy to see that the change isn’t really that profound, and actually represents one of the moments of wisdom and courage when Snyder and co. realized that they had to change what was written on the page in order to do it justice on the screen. If only they had done more of it.

They couldn’t have had a giant squid monster materialize in downtown New York, partially merging with buildings and people and leaving a swathe of destruction in its wake. More to the point, they shouldn’t. On the most basic level it would look simply ridiculous on film, more so than it did on the page, and that’s part of the point. Moore’s use of the squid monster necessarily pokes fun at the medium in which Watchmen was originally represented, just as with Adrian’s line “I’m not a Republic serial villain.” Part of the thematic structure of the original work was to at all times be aware of what it was, and to both critique and honour the medium as a way of telling human stories. Even this summation only scratches the surface of Moore’s narrative complexity, and because the film is a different medium than that of the comic book the effect would not be the same. Filmgoers are not used to seeing humans combat giant squid monsters, and so they would be drawn out of the experience in a way that would not have any historical or form related resonance. It was a very good idea to change the ending from the original one, and the changes that were made kept the thematic structure of the narrative largely intact.

The filmmakers effectively made Dr. Manhattan the “dark knight” of late 20th Century world politics. In a way it maintains what Watchmen always was: a story about how it takes a semi-divine scapegoat to serve as an immediate threat in order to unite humanity and save it from itself. In terms of design the ending works perfectly; in terms of its execution, however, there are some issues. The fact that they removed the final scene between Dr. Manhattan and Adrian is a poignant loss because it robs the latter of the humanity he finally achieved at that point in the book. After all his callous murdering and talk of necessary sacrifice, at the end of the novel Adrian shows self-doubt and despair as he questions “God” as to the whether or not he did “the right thing,” and it is in this action that he finally becomes a hero. His final appearance is as a tortured soul, simultaneously proud and ashamed of his actions, and in this he becomes a human being just like any of the other heroes of the story, meddling in grand, complex affairs in his attempts to be something more. Without this, Matthew Goode’s Adrian is only as good as the selected material allows him to be, and that leaves him far too clearly a villain for the purposes of Watchmen.

The attempt to cover the loss of this scene by putting Dr. Manhattan’s haunting final line, “Nothing ever ends,” into Laurie’s mouth just doesn’t work because her character doesn’t have the transcendent knowledge that gives the nonjudgmental utterance so much weight. This is descending to the level of nitpicking, I know, but the scene in question was a cornerstone in the construction of Watchmen, thematically, emotionally, character study-wise, etc., and to remove it without adequately compensating for the loss is a serious blow to the adaptation.

The film stumbles in the scenes following Adrian’s reveal of his plan because the movie struggles to remain frame-for-frame faithful to the graphic novel while at the same time coping with a dramatic change to the content and context of the original work. I maintain that it was a good idea to change the ending, and while the new ending has problems of its own they’re primarily a result of the overarching flaw in the design of the film adaptation: the filmmakers translate Watchmen in the most literal sense possible except for when they don’t. The ending is changed, subplots are lots, and in general the art is not the same despite constantly purporting to be. It tries to simultaneously leave the complex original work completely untouched and also reshape it into something that will work as a movie, and the end product feels fittingly uneven.

So in the end, did I like the movie? Sort of. It was enjoyable if strange to sit through, and I do intend to watch it again come the rumoured five-hour director’s cut. Clearly it was affecting enough to stimulate a rant of epic proportions. I think it’s a case of the unfilmable being filmed competently, though without taking any steps to make it any less unfilmable. It wasn’t bad, but it was misguided. I wish they had more profoundly changed the original text and tried to capture the spirit of the graphic novel, not the literal appearance. What we ended up with was something that looked a lot like Watchmen, and sometimes felt like it, but more often than not served only to remind us of what the original text achieved versus what the film does not. The basic idea of what Watchmen is could be translated to film, but it would necessarily be so drastically different that it would almost be unrecognizable. It would be something new altogether, but that wouldn’t make it unfaithful.

(Originally posted on Facebook on March 10th)